Let’s make a fictional company that employs workers in two levels:

- Senior worker: does important work; gets paid $50/hour.

- Principal worker: trusted with the most important work; gets paid $100/hour.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to differentiate the two levels! If a project completes early it might because of great work, or it might be because the project was under-scoped, or because corners were cut! A similar unknown applies to late and failed projects – we can’t directly attribute outcomes to the workers achieving them.

But over time we see trends. The very best workers anticipate problems and get important things done.

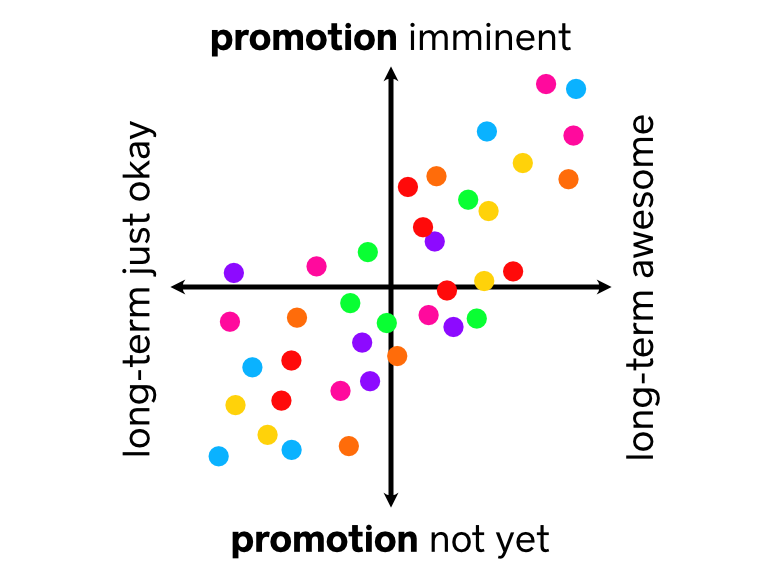

Next let’s interview 100 people and offer 40 of them jobs. We assume our interview process is great at identifying who to offer jobs to! But it’s not particularly good at assigning a level to each prospective hire. Here’s a scatter plot of employees with their interview scores (known) and long-term impact (unknown):

When we’re making a hiring decision, we only see the y-axis interview score. We need to wait a long term to learn a worker’s x-axis long-term performance.

We try our best. We give principal worker job offers to the ones that aced the interview, and senior worker job offers to the rest.

To complicate things further, our company isn’t the only fictional employer in town! There’s a bunch of other companies in the same industry with similar leveling systems and salaries.

Each interview yields a unique score for a candidate. Somebody who bombs our interview might ace the interview at our competitor’s! Or vice-versa. There’s lots of reasons for variability: perhaps a candidate slept better the night before the interview. Or the questions might fit a candidate’s experiences. Maybe an interviewer was having a great day!

Who Accepts Our Offer?

All else being equal, candidates will prefer a job at a higher level. If a candidate interviews at 4 companies, she might get 3 senior worker offers and one principal worker offer.

This dangerous bunch of candidates is particularly likely to accept an offer:

We give them principal worker salaries but they end up performing just okay. This is particularly offensive to each senior worker who is performing better.

Promoting the Best Workers

Though our interview process is loose, we are rigorous as fuck in our promotion process. Write up an exhaustive report with everything a particular senior worker has done and make the case that she’s worthy of the principal worker title.

Unfortunately, being rigorous as fuck takes time. We want to be extremely confident that Doris has earned her promotion! If she hasn’t, we’re diminishing the principal worker status symbol and losing an opportunity to promote someone more deserving.

Pay is Hard

I hate all of this.

I hate low-signal interviews. I hate how the second order effect of them encourages people to leave jobs they enjoy. But if you feel stuck at your current company, interviewing at 4 other companies may fix that!

I hate that promotion processes distract from serving customers. I especially hate how promotion processes attract workers to overly-complex solutions. ‘Only a principal worker could build this!’

Good Processes are Good

Improving an interview process is difficult, but I think it’s the best way forward here. Finding interview tools that match long-term performance is very difficult! At my non-fictional job we do take-home programming assignments; they’re much more predictive of programming ability.

Promo processes are also strategic. With an effective promo process, good people will stick-around in a job they like.

Though I’m a frequent interviewer, I haven’t much participated in improving these processes at my company. I’m very grateful to those who do.